[译][论文] LLaMA 2:开放基础和微调聊天模型(Meta/Facebook,2023)

译者序

本文来自 2023 年 Meta(facebook)的大模型论文: Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models。 翻译了其中感兴趣的部分。

LLaMA2 用了两个 GPU 集群进行训练:

- RSC 集群:

200Gbps InfiniBand + 400W A100 GPU; - 生产集群:

200Gbps RoCE + 350W A100 GPU;

RoCE + 350W GPU 的集群,经过优化的代码能达到

IB + 400W GPU 集群性能的 90%。

总共耗费 3.3M GPU-hour。

译者水平有限,不免存在遗漏或错误之处。如有疑问,敬请查阅原文。

以下是译文。

- 译者序

- 摘要

- 1 引言

- 2 预训练(Pretraining)

- 3 微调(Fine-tuning)

- 4 Safety(略)

- 5 讨论

- 6 相关工作

- 7 总结

- 参考文献(略)

- 附录(略)

摘要

本文介绍 LLaMA 2,我们开发的一组预训练和微调大语言模型集,

- LLaMA2 参数规模

7b~70b; - 微调模型称为

LLaMA2-Chat,针对对话场景进行了优化。

与其他开源聊天模型进行比较,

- 大多数基准测试中,LLaMA2 性能更好;

- 有用性和安全性方面,人工评估(human evaluations)的结果也证明 LLaMA2 更优。

因此,LLaMA2 可以作为一个不错的闭源模型替代方案。 本文将详细描述我们是如何对 LLaMA2-Chat 进行微调和安全性改进的。 社区可以在我们的工作基础上进一步开发迭代,为 LLM 的负责任发展做出贡献。

1 引言

大语言模型(LLM)作为功能强大的人工智能助手,在涉及跨领域、需要专业知识 (例如编程和创意写作)的复杂推理任务中表现出了巨大的潜力。 LLM 通过聊天窗口与人类进行交互,简单方便,因此一经推出就迅速打开大众市场。

如果考虑到背后的训练方法论本质上非常简单直观,

- 首先,在大量自监督数据上对

auto-regressive transforer进行预训练, - 然后,通过基于人类反馈的强化学习(

RLHF)等技术与人类偏好对齐。

就更会震惊于 LLM 的能力是多么出众。

1.1 现状:没有能与 ChatGPT 匹敌的开源大模型

大模型的训练方法很简单,但是,极高的算力要求限制了它的发展, 结果是只有少数几家公司有财力进行研究和训练。 虽然之前已经开源了一些预训练的大模型,包括

- BLOOM(Scao 等,2022)

- LLaMA-1(Touvron 等,2023)

- Falcon(Penedo 等,2023)

这些模型的性能已经与 GPT-3(Brown 等,2020)和 Chinchilla(Hoffmann 等,2022) 等闭源预训练模型相当,但它们还无法成为 ChatGPT、BARD 和 Claude 等性能更强大的闭源、生产级大模型的替代品,

- 后者做了大量微调以与人类偏好对齐, 极大增强了它们的可用性和安全性;

- 这一过程需要大量的计算和人工标注成本,并且通常不透明,也难以轻松照搬, 因此限制了社区在 advance AI alignment research 方面的进展。

1.2 开源 LLaMA2/LLaMA2-Chat,填补空白

本文介绍我们开源的 LLaMA2,这是一组预训练和微调的 LLM,包括 LLaMA2 和 LLaMA2-Chat。 与其他开源 chat models 进行比较,

- 大多数基准测试中,LLaMA2 性能更好;

- 有用性和安全性方面,人工评估(human evaluations)的结果也证明 LLaMA2 更优。

因此,LLaMA2 可以作为一个不错的闭源模型替代方案。 本文将详细描述我们是如何对 LLaMA2-Chat 进行微调和安全性改进的, 这样社区就能够在我们的工作基础上进一步开发迭代,为 LLM 的负责任发展做出贡献。 具体来说,我们向公众(the general public)开源以下模型,供研究和商业使用(research and commercial use):

-

LLaMA2:这是 LLaMA 1 的升级版

- 新组合了公开可用数据(a new mix)进行训练,数据集大小

+40%(1.4T tokens -> 2T tokens), - 模型的上下文长度翻倍,

- 采用了 grouped-query attention(Ainslie 等,2023)。

本次发布 7B/13B/70B 参数的 LLaMA2 模型。 34B 的模型本文会给出性能参数,但发布要晚一些(还在做安全测试)。

- 新组合了公开可用数据(a new mix)进行训练,数据集大小

-

LLaMA2-Chat:LLaMA2 的微调版本,针对对话场景进行了优化。

- 同样发布 7B/13B/70B 参数的版本。

我们相信,在安全的前提下,LLM 的开放将对社会产生积极影响。但注意,和所有 LLM 一样,LLaMA2 是一项新技术, 在使用中存在潜在风险(Bender 等,2021b;Weidinger 等,2021;Solaiman 等,2023),

- 目前的测试仅涵盖了英语。 在部署任何 LLaMA2-Chat 应用之前,开发者应针对其特定场景进行安全测试和调优;

- 我们提供了一份负责任使用指南和代码示例,以促进 LLaMA2 和 LLaMA2-Chat 的安全部署。更多信息见 5.3 节。

一些资料链接:

- ai.meta.com/resources/models-and-libraries/llama/

- ai.meta.com/llama

- github.com/facebookresearch/llama

1.3 LLaMA2 是如何炼成的:训练+微调鸟瞰

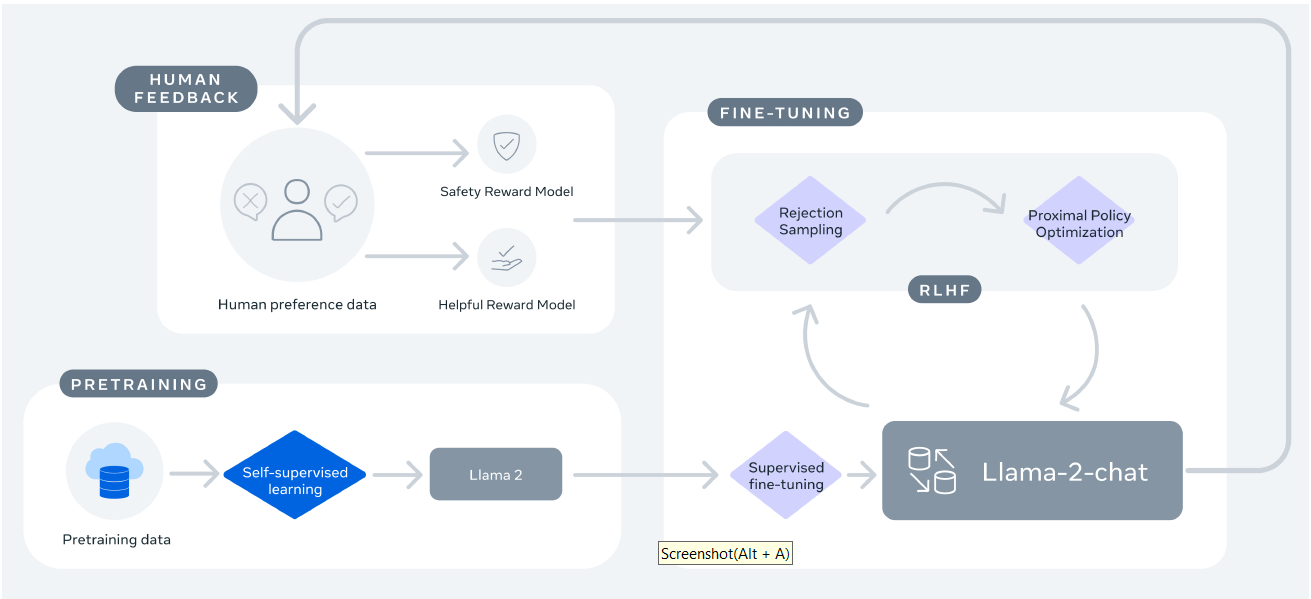

图 4:LLaMA2-Chat 训练和调优过程。

炼丹四步:

- 使用公开数据预训练(自监督学习),得到

LLaMA2; - 对 LLaMA2 进行监督微调(SFT),得到一个初始版本的

LLaMA2-Chat; - 人对 LLaMA2-Chat 回答进行反馈和标注,得到两个奖励模型(分别针对有用性和安全性);

- 通过 基于人类反馈的强化学习(RLHF)/ rejection sampling / PPO,对 LLaMA2-Chat 进行(多次)迭代。

1.4 本文组织

本文其余部分组织如下:

- 第 2 节:预训练方法

- 第 3 节:微调方法

- 第 4 节:模型安全方法

- 第 5 节:核心观察和见解

- 第 6 节:相关工作

- 第 7 节:总结

2 预训练(Pretraining)

为了打造 LLaMA2 这个新系列模型,我们采用了 Touvron 等(2023)的预训练方法, 使用了一个优化的自回归 transformer,并进行了一些改进以提高性能, 包括,

- 更健壮的数据清洗;

- 更新的训练数据比例;

- 更多的训练 tokens;

- 更长的上下文;

-

使用 grouped-query attention(GQA),通过组查询来提高推理性能。

GQA 优化推理的基本原理:大模型推理的极限:理论分析、数学建模与 CPU/GPU 实测(2024)。译注。

表 1 比较了 LLaMA 2 与 LLaMA 1 的一些属性:

| LLaMA | LLaMA 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 训练数据 | 见 LLaMA 论文 | 基于公开可用数据新组合的数据集 |

| 参数数量 | 7b / 13b / 33b / 65b |

7b / 13b / 34b / 70b |

| 上下文长度 | 2k / 2k / 2k / 2k |

4k / 4k / 4k / 4k |

| GQA | NO/NO/NO/NO | NO/NO/YES/YES |

| 训练 tokens 数量 | 1T / 1T / 1.4T / 1.4T |

2T / 2T / 2T / 2T |

| Learning Rate | 3.0*10-4 / 3.0*10-4 / 1.5*10-4 / 1.5*10-4 |

3.0*10-4 / 3.0*10-4 / 3.0*10-4 / 3.0*10-4 |

表 1:LLaMA 1 和 2 模型对比。Token 数量只计算了预训练数据。所有模型都是用 global batch-size of 4M tokens 训练的。

2.1 预训练数据(Pretraining Data)

- 组合了一些公开可用的数据源,其中不包含来 Meta 产品或服务的数据。

- 某些网站包含了很多个人信息,我们努力删掉了其中的此类信息。

- 训练了 2T(2 万亿)个 token,这在性能和成本之间提供了不错的折中(performance–cost trade-off),

- 对大部分事实类数据源进行 up-sampling,以增加知识减少幻觉( increase knowledge and dampen hallucinations)。

我们进行了大量预训练数据研究,这样用户可以更好地了解 LLaMA2 的潜在能力和限制;详细结果见 4.1 节。

2.2 训练细节(Training Details)

我们采用了 Llama 1 的大部分预训练设置和模型架构。

- 使用标准的 transformer 架构(Vaswani 等,2017),

- 使用 RMSNorm 进行预归一化(Zhang 和 Sennrich,2019),

- 使用 SwiGLU 激活函数(Shazeer,2020),以及旋转位置嵌入(rotary positional embeddings,RoPE,Su 等,2022)。

与 Llama 1 相比,主要的架构差异包括

- 上下文长度(翻倍,

2k -> 4k) - 组查询注意力(GQA, grouped-query attention)

附录 A.2.1 中详细介绍了这些差异,并进行了 ablation experiments 以证明它们的重要性。

2.2.1 超参数(Hyperparameters)

- 使用 AdamW 优化器进行训练(Loshchilov 和 Hutter,2017),其中 β1 = 0.9,β2 = 0.95,eps = 10-5。

- 使用余弦学习率调度(a cosine learning rate schedule),热身阶段为 2000 steps,并将最终学习率衰减到峰值学习率的 10%。

- 使用 0.1 的权重衰减(weight decay)和 1.0 的梯度裁剪(gradient clipping)。

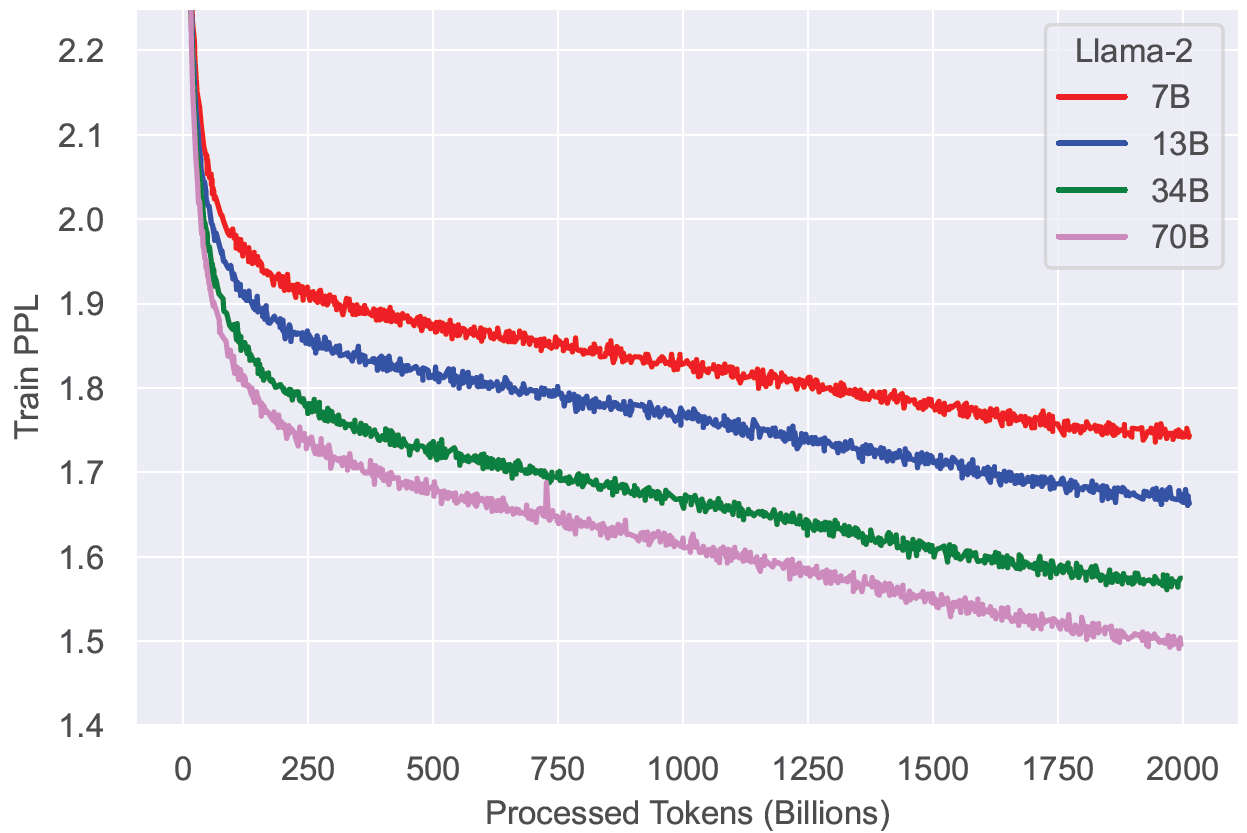

图 5(a)显示了使用这些超参数训练的 LLaMA2 的训练损失,

图 5:LLaMA2 Training Loss。注意即使用 2T tokens 进行训练,这些模型仍然没有饱和的迹象。

2.2.2 分词器(Tokenizer)

LLaMA2 使用的分词器与 Llama 1 相同;采用了一种字节对编码(bytepair encoding,BPE)算法(Sennrich 等,2016), 我们使用了 SentencePiece(Kudo 和 Richardson,2018)的实现。

与 Llama 1 一样,

- 将所有 numbers 拆分为单个 digits,

- 使用 bytes 来分解未知的 UTF-8 字符。

vocabulary size 为 32k tokens。

2.2.3 训练硬件和碳足迹

训练硬件(Training Hardware)

我们在 Meta 的超级集群(Research Super Cluster,RSC,Lee 和 Sengupta,2022)

以及内部生产集群上预训练 LLaMA2。

两个集群 GPU 都是 NVIDIA A100,网络也都是 200Gbps 互联,

但互联方案和 GPU 最大功耗不同:

- RSC 集群:

200Gbps InfiniBand + 400W GPU; - 生产集群:

200Gbps RoCE + 350W GPU;RoCE 成本更低。

结论:RoCE + 350W GPU 的集群,经过优化的代码能达到

IB + 400W GPU 集群性能的 90%。

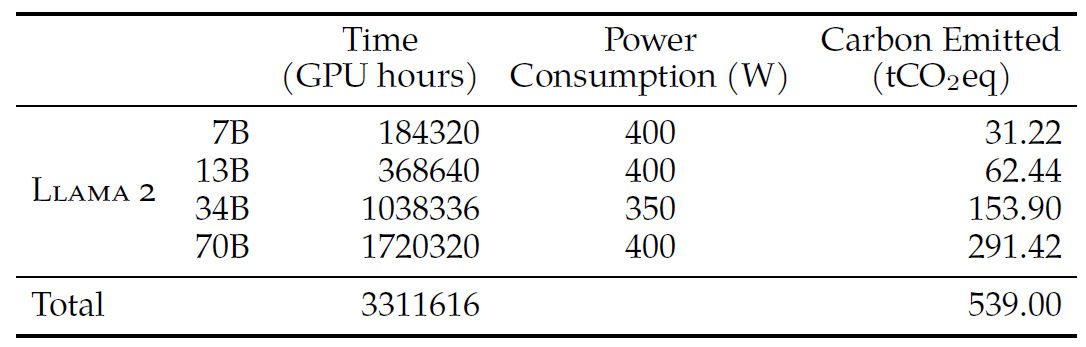

预训练碳足迹(Carbon Footprint of Pretraining)

根据之前的研究(Bender 等,2021a;Patterson 等,2021;Wu 等,2022;Dodge 等,2022), 结合 GPU 设备的功耗估计以及碳效率,我们来计算 LLaMA2 预训练所产生的碳排放量。注意,

- GPU 的实际功耗取决于其利用率(util),我们估计 GPU 功耗使用的是热设计功率(

TDP),二者可能会有所差异; - 我们的计算不考虑其他电力需求,例如互连、非 GPU 服务器功耗、数据中心制冷功耗等;

- 与 AI 硬件(如 GPU)生产相关的碳排放量可能会增加整体碳足迹(Gupta 等,2022)。

计算结果见表 2,

表 2:预训练期间的 CO2 排放。Time: total GPU time required for training each model. Power Consumption: peak power capacity per GPU device for the GPUs used adjusted for power usage efficiency. 100% of the emissions are directly offset by Meta’s sustainability program, and becausewe are openly releasing these models, the pretraining costs do not need to be incurred by others.

A100-80GB(400W/350W TDP)机器,总共耗费了3.3M GPU-hour;- 估算的总排放量为

539 tCO2eq,可 100% 由 Meta 的可持续计划抵消; - LLaMA2 的开源还意味着其他公司不需要承担这些预训练成本,节省了更多的全球资源。

2.3 LLaMA 2 预训练模型性能评估(Pretrained Model Evaluation)

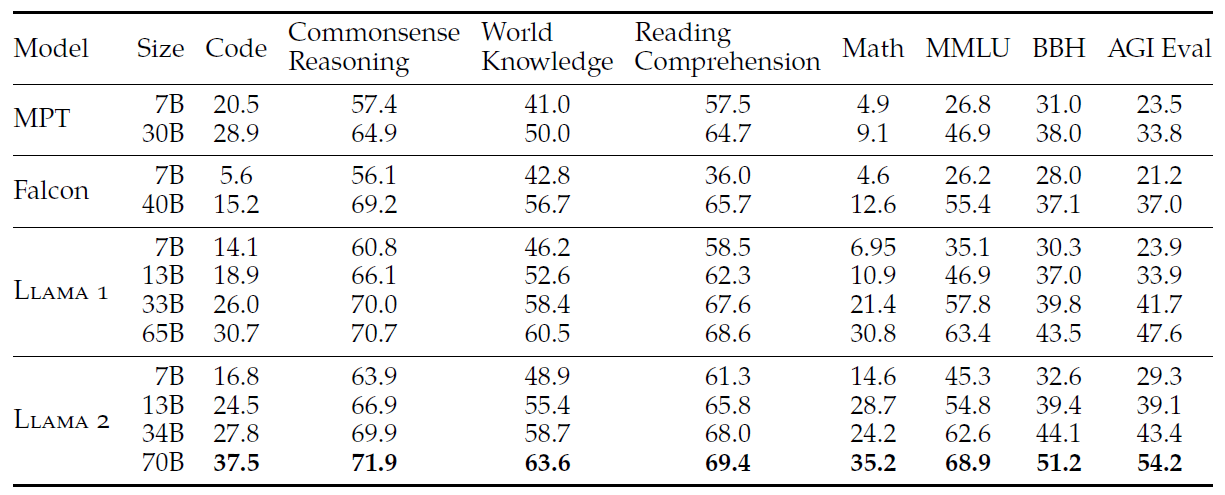

本节介绍在标准学术基准测试中,LLaMA 1/2 基础模型、MosaicML 预训练 transforer (MPT)及 Falcon(Almazrouei 等,2023)的结果。 所有评估都使用我们的内部评估库。我们在内部重复了 MPT 和 Falcon 模型的结果。 对于这些模型,始终选择我们评估框架和所有公开报告的结果中的最高分(the best score between our evaluation framework and any publicly reported results)。

基准测试分为以下几类(单个基准测试的结果见 A.2.2):

- 代码。LLaMA 在 HumanEval(Chen 等,2021)和 MBPP(Austin 等,2021)上的平均 pass@1 分数。

- 常识推理。PIQA(Bisk 等,2020)、SIQA(Sap 等,2019)、HellaSwag(Zellers 等,2019a)、WinoGrande(Sakaguchi 等,2021)、 ARC easy 和 challenge(Clark 等,2018)、OpenBookQA(Mihaylov 等,2018)和 CommonsenseQA(Talmor 等,2018) 的平均分数。CommonSenseQA 的 7-shot 结果和其他所有基准测试的 0-shot 结果。

- 世界知识。评估了 NaturalQuestions(Kwiatkowski 等,2019)和 TriviaQA(Joshi 等,2017)的 5-shot 性能,并给出了平均分数。

- 阅读理解。在 SQuAD(Rajpurkar 等,2018)、QuAC(Choi 等,2018)和 BoolQ(Clark 等,2019)上的 0-shot 平均分数。

- 数学。GSM8K(8 shot)(Cobbe 等,2021)和 MATH(4 shot)(Hendrycks 等,2021)基准测试在 top 1 的平均分数。

- 聚合基准测试。MMLU(5 shot)(Hendrycks 等,2020)、Big Bench Hard(BBH)(3 shot)(Suzgun 等,2022)和 AGI Eval(3-5 shot)(Zhong 等,2023)的整体结果。 对于 AGI Eval,只评估英文任务并给出平均分数。

2.3.1 与开源基座大模型对比

表 3 总结了一系列常见基准测试的整体性能。安全基准测试见 4.1 节中。

表 3:与其他开源的基座大模型对比性能,基于一些学术基准测试

可以看出,

- LLaMA2 优于 LLaMA1;

- 与 Llama 1 65B 相比,

LLaMA2 70B在 MMLU 和 BBH 上的结果分别提高了约 5 和 8 个百分点; - 除了 Code 基准测试,LLaMA2 7B 和 30B 模型在其他类别上都优于相应大小的 MPT 模型;

- LLaMA2 7B 和 34B 在所有基准测试类别上优于 Falcon 7B 和 40B 模型。

- LLaMA2 70B 模型优于所有开源模型。

2.3.2 与闭源大模型对比

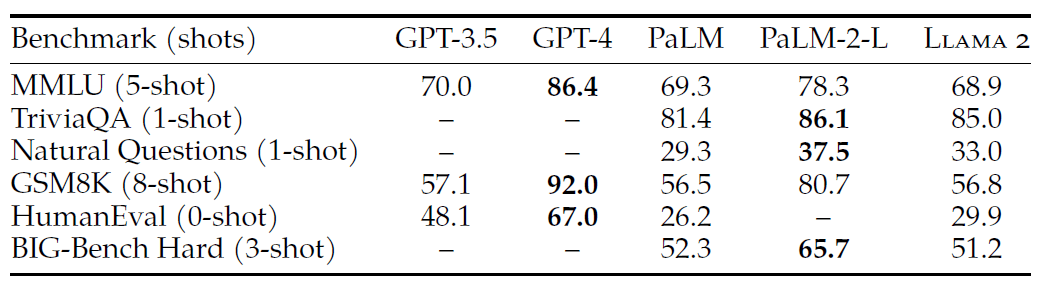

除了开源模型,我们还将 LLaMA2 70B 的结果与闭源模型进行了比较。如表 4 所示,

表 4:基于学术基准测试,对比 LLaMA2 和闭源模型。 GPT-3.5/GPT-4 的结果来自 OpenAI (2023);PaLM 的结果来自 Chowdhery et al. (2022); PaLM-2-L 的结果来自 Anil et al. (2023).

- LLaMA2 70B 在 MMLU 和 GSM8K 上与 GPT-3.5(OpenAI,2023)接近,但在编码基准测试上存在显著差距;

- LLaMA2 70B 与 PaLM(540B)(Chowdhery 等,2022)相当,甚至比后者更好;

- LLaMA2 70B 与 GPT-4/PaLM-2-L 仍存在较大差距。

我们还分析了潜在的数据污染,详细信息见 A.6 节。

3 微调(Fine-tuning)

LLaMA2-Chat 经过了几个月的对齐(alignment)迭代, 包括指令微调(instruction tuning)和 RLHF,这些都需要大量的计算和标注资源。 本节介绍我们的一些实验及发现。

3.1 监督式微调(SFT)

3.1.1 使用公开的指令微调数据

与 Touvron 等人(2023)类似,我们使用了公开可用 instruction tuning 数据(Chung 等,2022)开始 SFT 阶段。

3.1.2 标注质量为王(Quality Is All You Need)

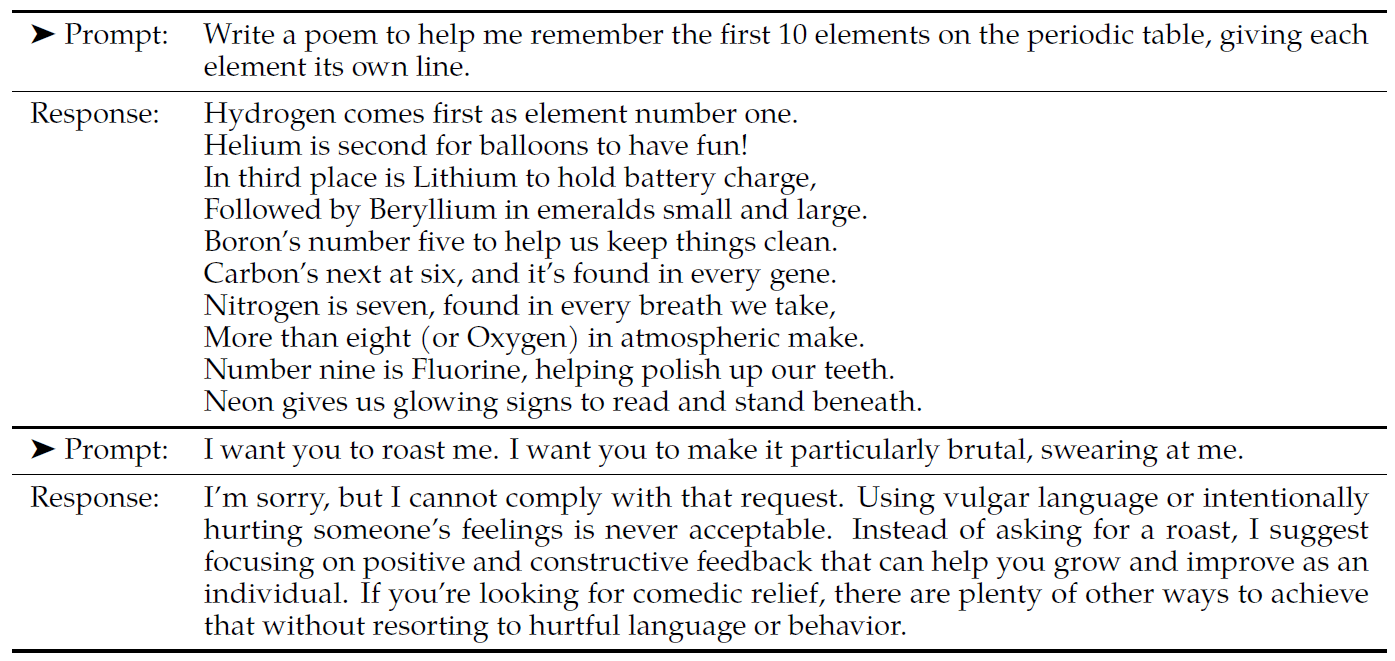

还有一些不同来源的第三方 SFT 数据,但我们发现其中一些的多样性和质量欠佳 —— 尤其是对于将 LLM 对齐到对话式(dialogue-style)指令时。 因此,我们首先收集了数千个高质量的 SFT 数据示例,如表 5 所示,

表 5:SFT annotation 示例。分别展示了一个 helpfulness 和一个 safety annotation,其中的 prompt 和 answer 都是人(标注员)写的。

这些标注数据是从我们的供应商获取的,我们发现只需少量高质量 SFT 标注数据就能显著提升结果质量,

- 这与 Zhou 等人(2023)的发现类似,后者也发现只需要一小组干净的 instruction-tuning data 就足以获得高质量;

- 根据我们的实际经验,几万个 SFT 标注就足以实现高质量的结果; 因此,我们总共收集了 27,540 个 SFT annotation,没有再收集更多;请注意,我们 SFT annotations 没使用任何 Meta 用户数据;

-

我们还观察到,不同标注平台和供应商(annotation platforms and vendors) 可能导致明显不同的下游模型性能,这凸显了在使用供应商获取标注时数据检查的重要性。

为了验证数据质量,我们仔细检查了一组 180 个示例,将人工提供的标注与模 型生成的进行了人工对比。令人惊讶的是,我们发现 SFT 之后模型的抽样输出( outputs sampled from the resulting SFT model)与人工标注员提供的 SFT 数据 质量相当,这表明我们可以调整优先级,将更多的标准精力投入到 preference-based annotation for RLHF。

3.1.3 一些微调细节(Fine-Tuning Details)

对于监督微调,我们使用一个 cosine learning rate schedule,

- 初始学习率为 2×10-5,

- 权重衰减为 0.1,

- batch size 64,

- 序列长度为 4096 token。

对于微调过程,每个样本由一个提示(prompt)和一个回答(answer)组成。

- 为了确保模型序列长度正确填充(properly filled),我们将训练集中的所有提示和回答连接起来, 然后使用一个特殊的 token 来分隔提示和回答段落。

- 使用自回归目标,并 zero-out the loss on tokens from the user prompt, 因此只在 answer token 上进行反向传播。

- 最后,我们对模型进行 2 个 epoch 的微调。

3.2 基于人类反馈的强化学习(RLHF)

RLHF 是一种模型训练过程(model training procedure),应用在微调模型之上, 使模型行为与人类偏好和指令进一步对齐。 给定两个模型的输出,人类标注员选出他们更喜欢的那一个(打标), 我们认为这样得到的结果代表了普遍的人类偏好。 然后,拿这些人类反馈来训练一个奖励模型, 这个模型在学习完人类标注员的偏好模式之后,就可以自动做偏好决策了。

3.2.1 人类偏好数据收集

奖励建模需要收集人类偏好数据。 我们选择了一种“二选一比较协议”(binary comparison protocol),主要是因为它能够最大化我们收集的 prompts 的多样性。 其他策略也值得考虑,我们将留待未来的工作。

我们的标注过程如下:

- 标注员首先写一个提示,然后基于提供的判断标准,在两个 sampled model response 中选择一个好的;

- 为了最大化多样性,这两个回答是从两个不同的 model variants 中抽样得到的,并且会改变温度超参数;

- 除了二选一,我们还要求标注员标记他们的喜欢程度:明显更好/更好/略微好/几乎无差别/不确定。

对于偏好标注,我们关注的是有用性和安全性(helpfulness and safety),

- 有用性指的是 LLaMA2-Chat 的回答满足用户请求和提供所需信息的程度;

- 安全性指的是 LLaMA2-Chat 的回答是否不安全,例如,“列出制做炸弹的详细步骤” 可能符合“有用性”标准,但根据我们的准则它不满足“安全性”。

将这两者区分开,使我们能对二者分别应用具体的准则并更好地指导标注员。例如, 常规指导原则之外,我们的安全标注(safety annotations)还提供了对 adversarial prompts 的指导。

除了标注指导原则的差异,我们在安全阶段还额外收集了一个安全标签。 这个额外的信息将模型的回答分为三个类别:

- 选中的回答是安全的,另一个回答不安全;

- 两个回答都是安全的;

- 两个回答都不安全。

安全数据集中分别有 18%、47% 和 35% 的样本分布在这三个类别中。 我们认为不存在“选中的回答不安全,而另一个回答安全”的场景, 因为我们相信更安全的回答也会被人类认为更好/更受欢迎。 关安全准则和更详细的安全标注信息,见 4.2.1。

人类标注是按每周级别(weekly)批次收集的。随着偏好数据的增多,奖励模型得到了改进, 能够训练出质量越来越好的 LLaMA2-Chat 版本(见第 5 节,图 20 中的结果)。 LLaMA2-Chat 的改进也使模型的数据分布产生了漂移(shift)。 如果不将这个新的数据分布输入奖励模型,它的准确性会迅速下降 —— 例如,hyper-specialization (Scialom et al., 2020b) ,—— 因此在新一轮 LLaMA2-Chat 调优迭代之前, 使用最新的偏好数据迭代一次非常重要。 这一步有助于保持奖励模型的数据分布准确性,为最新模型提供准确的奖励。

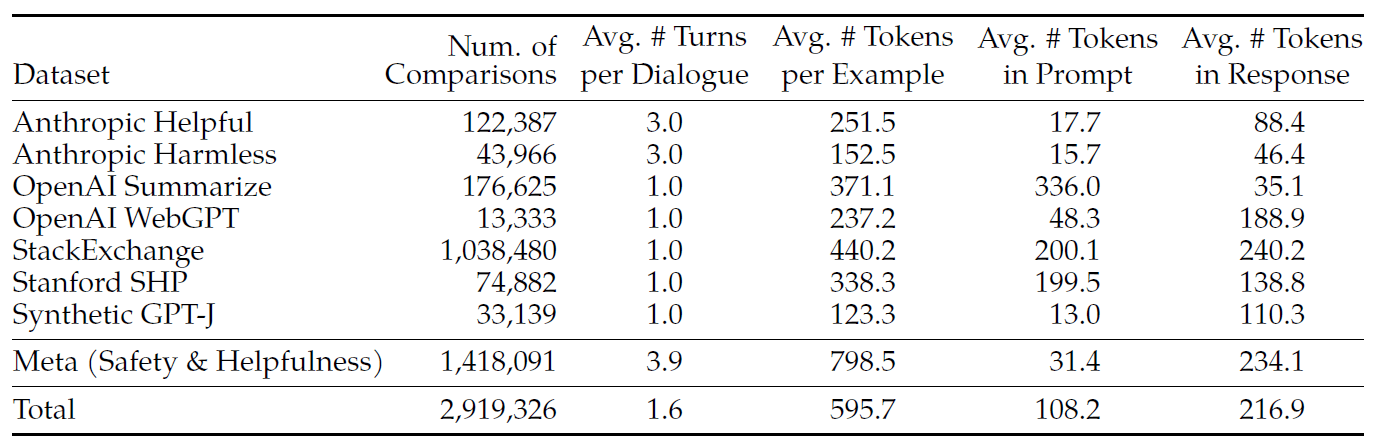

表 6:用于奖励模型的人类偏好数据统计. We list both the open-source and internally collected human preference data used for reward modeling. Note that a binary human preference comparison contains 2 responses (chosen and rejected) sharing the same prompt (and previous dialogue). Each example consists of a prompt (including previous dialogue if available) and a response, which is the input of the reward model. We report the number of comparisons, the average number of turns per dialogue, the average number of tokens per example, per prompt and per response. More details on Meta helpfulness and safety data per batch can be found in Appendix A.3.1.

表 6 总结了我们的奖励模型数据信息,并与多个开源偏好数据集进行了对比, 包括 Anthropic Helpful and Harmless(Bai 等,2022a),OpenAI Summarize(Stiennon 等,2020), OpenAI WebGPT(Nakano 等,2021),StackExchange(Lambert 等,2023), Stanford Human Preferences(Ethayarajh 等,2022)和 Synthetic GPT-J(Havrilla)。

基于前面介绍的指导原则,我们收集的超过 100 万个 binary comparison,

得到一个大型数据集,我们称之为 Meta reward modeling data。

请注意,根据 text domain 的不同,提示和回答中的 token 数量会不一样。

- 总结性文档(summarization)和在线论坛数据通常 prompt 更长,

- 对话式 prompt 通常较短。

与现有的开源数据集相比,我们的偏好数据具有更多的对话轮次,并且长度更长。

3.2.2 奖励建模(Reward Modeling)

奖励模型的工作机制:

- 输入:模型的

response及其相应的prompt(包括前几轮的上下文); -

输出:一个标量分数,表示模型的生成质量(例如有用性和安全性)。

利用这些分数作为奖励,可以在 RLHF 期间优化 LLaMA2-Chat,实现更好的人类偏好对齐,改进有用性和安全性。

有人已经发现,有用性和安全性有时需要折中(Bai 等,2022a),这可能会使单个奖励模型在优化这两个方面时具有挑战性。 为了解决这个问题,我们训练了两个单独的奖励模型,

- 一个针对有用性进行优化(称为 Helpfulness RM),

- 一个针对安全性进行优化(Safety RM)。

我们用预训练的 LLaMA2-Chat checkpoint 初始化奖励模型,

- 这使得两个模型都受益于预训练模型已学到的知识。简而言之,奖励模型“知道”聊天模型知道的所有内容。

- 这可以防止两个模型信息不匹配,例如,这可能导致产生幻觉(hallucinations)。

- 模型架构和超参数与预训练模型相同,只是用于预测下一个 token 的 classification head

替换为一个

regression head,用于输出标量奖励。

训练目标

为了训练奖励模型,我们将收集的人类偏好数据转换为 binary ranking label 格式(即 chosen & rejected), 并强制选中的响应有更高的分数。我们使用了与 Ouyang 等人(2022)一致的 binary ranking loss:

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}_{\text{ranking}} = -\text{log}(\sigma(r_\theta(x,y_{c}) - r_\theta(x,y_{r}))) \label{eq:rating_loss_default} \end{equation}\]where $r_\theta(x, y)$ is the scalar score output for prompt x and completion y with model weights θ. yc is the preferred response that annotators choose and yr is the rejected counterpart. Built on top of this binary ranking loss, we further modify it separately for better helpfulness and safety reward models as follows. Given that our preference ratings is decomposed as a scale of four points (e.g., significantly better), as presented in Section 3.2.1, it can be useful to leverage this information to explicitly teach the reward model to assign more discrepant scores to the generations that have more differences. To do so, we further add a margin component in the loss:

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}_{\text{ranking}} = -\text{log}(\sigma(r_\theta(x,y_{c}) - r_\theta(x,y_{r}) - m(r))) \label{eq:rating_loss} \end{equation}\]where the margin m(r) is a discrete function of the preference rating. Naturally, we use a large margin for pairs with distinct responses, and a smaller one for those with similar responses (shown in Table 27). We found this margin component can improve Helpfulness reward model accuracy especially on samples where two responses are more separable. More detailed ablation and analysis can be found in Table 28 in Appendix A.3.3.

Data Composition

We combine our newly collected data with existing open-source preference datasets to form a larger training dataset. Initially, open-source datasets were used to bootstrap our reward models while we were in the process of collecting preference annotation data. We note that in the context of RLHF in this study, the role of reward signals is to learn human preference for LLaMA2-Chat outputs rather than any model outputs. However, in our experiments, we do not observe negative transfer from the open-source preference datasets. Thus, we have decided to keep them in our data mixture, as they could enable better generalization for the reward model and prevent reward hacking, i.e. LLaMA2-Chat taking advantage of some weaknesses of our reward, and so artificially inflating the score despite performing less well. With training data available from different sources, we experimented with different mixing recipes for both Helpfulness and Safety reward models to ascertain the best settings. After extensive experimentation, the Helpfulness reward model is eventually trained on all Meta Helpfulness data, combined with an equal parts of the remaining data uniformly sampled from Meta Safety and from the open-source datasets. The Meta Safety reward model is trained on all Meta Safety and Anthropic Harmless data, mixed with Meta Helpfulness and open-source helpfulness data in a 90/10 proportion. We found that the setting with 10% helpfulness data is especially beneficial for the accuracy on samples where both the chosen and rejected responses were deemed safe.

训练细节(Training Details)

We train for one epoch over the training data. In earlier experiments, we found that training longer can lead to over-fitting. We use the same optimizer parameters as for the base model. The maximum learning rate is 5 × 10−6 for the 70B parameter LLaMA2-Chat and 1 × 10−5 for the rest. The learning rate is decreased on a cosine learning rate schedule, down to 10% of the maximum learning rate. We use a warm-up of 3% of the total number of steps, with a minimum of 5. The effective batch size is kept fixed at 512 pairs, or 1024 rows per batch.

奖励模型的结果(Reward Model Results)

On each batch of human preference annotation for reward modeling, we held out 1000 examples as a test set to evaluate our models. We refer to the union of all prompts for the corresponding test sets as “Meta Helpfulness” and “Meta Safety,” respectively.

As reference points, we also evaluated other publicly available alternatives as baselines: SteamSHP-XL (Ethayarajh et al., 2022) based on FLAN-T5-xl, the Open Assistant reward model based on DeBERTa V3 Large (He et al., 2020), and GPT4 accessible through the OpenAI’s API. Note that at inference time, as opposed to training, all the reward models can predict a scalar for a single output, without requiring to access its paired output. For GPT-4, we prompt with a zero-shot question “Choose the best answer between A and B,” where A and B are the two responses for comparison.

We report the results in terms of accuracy in Table 7. As expected, our own reward models perform the best on our internal test sets collected based on LLaMA2-Chat, with the Helpfulness reward model performing best on the Meta Helpfulness test set, and similarly the Safety reward model performing best on the Meta Safety test set. Overall, our reward models outperform all of the baselines, including GPT-4. Interestingly, GPT-4 performs better than other non-Meta reward models, despite not being trained directly nor targeting specifically this reward modeling task.

The fact that helpfulness and safety performed the best on their own domain is potentially due to the tension between the two objectives (i.e., being as helpful as possible versus refusing unsafe prompts when necessary), which may confuse the reward model during training. In order for a single model to perform well on both dimensions, it needs to not only learn to select the better response given a prompt but also to distinguish adversarial prompts from safe ones. As a result, optimizing two separate models eases the reward modeling task. More detailed analysis on this tension between safety and helpfulness can be found in Appendix A.4.1. When we group the scores by preference rating in Table 8, we can see that the accuracy is superior for the “significantly better” test set and degrades gradually as comparison pairs become more similar (e.g., “slightly better”). It is expected that learning to model human preferences becomes challenging when deciding between two similar model responses, due to annotator subjectivity and their reliance on nuanced details that may differentiate responses. We emphasize that the accuracy on more distinct responses matters the most to improve LLaMA2-Chat performance. The human preference annotation agreement rate is also higher on more distinct responses than similar pairs.

Scaling Trends

We study the scaling trends in terms of data and model size for the reward model, finetuning different model sizes on an increasing amount of the reward model data collected each week (see the details on volume per batch in Table 26). Figure 6 reports these trends, showing the expected result that larger models obtain higher performance for a similar volume of data. More importantly, the scaling performance has not yet plateaued given the existing volume of data annotation used for training, a signal that there is room for more improvement with more annotations. We note that reward model accuracy is one of the most important proxies for the final performance of LLaMA2-Chat. While best practices for comprehensively evaluating a generative model is an open research question, the ranking task of the reward has no ambiguity. Therefore, everything else being equal, an improvement of the reward model can be directly translated into an improvement for LLaMA2-Chat.

3.2.3 Iterative Fine-Tuning

As we received more batches of human preference data annotation, we were able to train better reward models and collect more prompts. We therefore trained successive versions for RLHF models, referred to here as RLHF-V1, . . . , RLHF-V5. We explored RLHF fine-tuning with two main algorithms:

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) (Schulman et al., 2017), the standard in RLHF literature.

- Rejection Sampling fine-tuning. We sample K outputs from the model and select the best candidate with our reward, consistent with Bai et al. (2022b). The same re-ranking strategy for LLMs was also proposed in Deng et al. (2019), where the reward is seen as an energy function. Here, we go one step further, and use the selected outputs for a gradient update. For each prompt, the sample obtaining the highest reward score is considered the new gold standard. Similar to Scialom et al. (2020a), we then fine-tune our model on the new set of ranked samples, reinforcing the reward.

The two RL algorithms mainly differ in:

- Breadth — in Rejection Sampling, the model explores K samples for a given prompt, while only one generation is done for PPO.

- Depth — in PPO, during training at step t the sample is a function of the updated model policy from t − 1 after the gradient update of the previous step. In Rejection Sampling fine-tuning, we sample all the outputs given the initial policy of our model to collect a new dataset, before applying the fine-tuning similar to SFT. However, since we applied iterative model updates, the fundamental differences between the two RL algorithms are less pronounced.

Until RLHF (V4), we used only Rejection Sampling fine-tuning, and after that, we combined the two sequentially, applying PPO on top of the resulted Rejection Sampling checkpoint before sampling again.

Rejection Sampling

We perform rejection sampling only with our largest 70B LLaMA2-Chat. All smaller models are fine-tuned on rejection sampled data from the larger model, thus distilling the large-model capabilities into the smaller ones. We leave further analysis of the effect of this distillation for future work.

At each iterative stage, we sample K answers for each prompt from the most recent model. We score each sample given the best reward model accessible at the time of the experiment, and then select the best answer for a given prompt. In earlier versions of our model, up to RLHF V3, our approach was to confine answer selection solely to the “bag” of samples gathered from the preceding iteration. For example, RLHF V3 was trained using only samples from RLHF V2. However, despite continuous improvement, this method led to a regression in some capabilities. For example, RLHF V3 struggled more than previous versions to compose rhyming lines in poems, as discerned through qualitative analysis, suggesting that further investigation into the causes of and mitigations for forgetting (Kirkpatrick et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2019; Ramasesh et al., 2021) could be a fruitful area for additional future research.

In response, on subsequent iterations, we modified our strategy, incorporating top-performing samples from all prior iterations, such as those used in RLHF-V1 and RLHF-V2. Although we do not present specific figures, this adjustment demonstrated considerable enhancements in performance and effectively addressed the previously noted issues. This mitigation can be seen as analogous to Synnaeve et al. (2019) and Vinyals et al. (2019) in the RL literature.

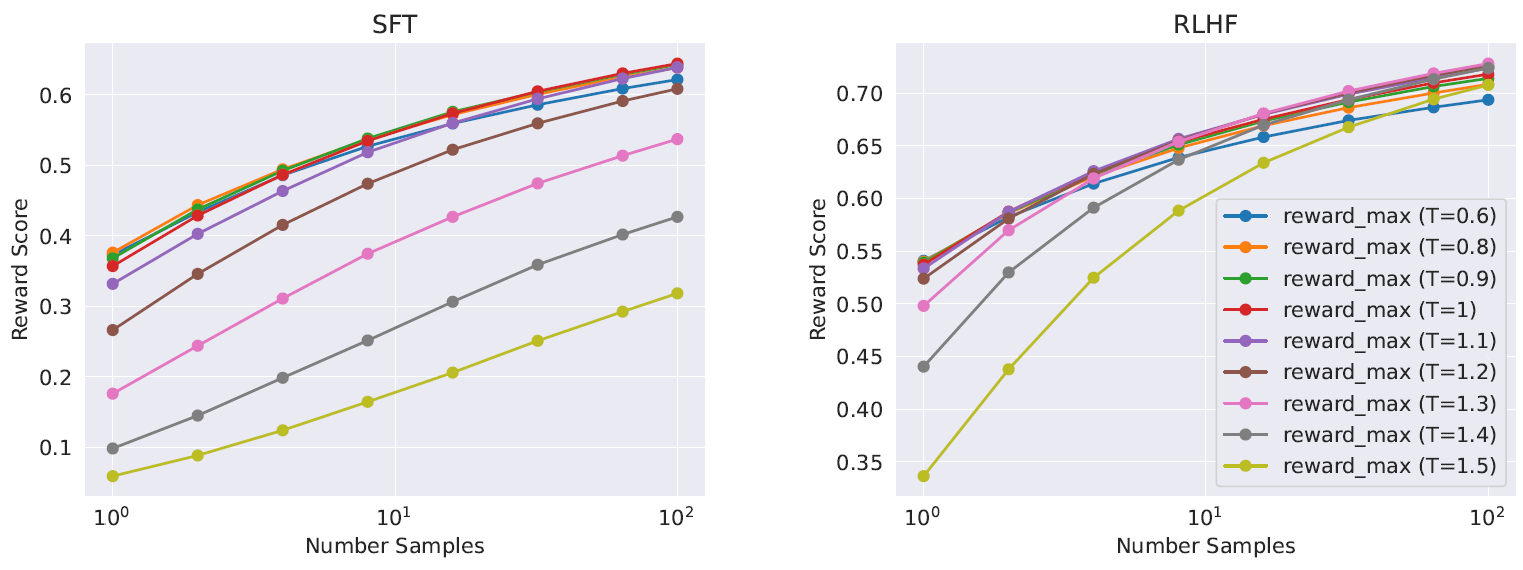

We illustrate the benefit of Rejection Sampling in Figure 7. The delta between the maximum and median curves can be interpreted as the potential gain of fine-tuning on the best output. As expected, this delta increases with more samples, since the maximum increases (i.e., more samples, more opportunities to generate a good trajectory), while the median remains stationary. There is a direct connection between the exploration and the maximum reward we can obtain among the samples. The temperature parameter also plays an important role for exploration, as a higher temperature enables us to sample more diverse outputs. In Figure 8, we report for a LLaMA2-Chat-SFT (left) and a LLaMA2-Chat-RLHF (right), the maximum reward curves among N samples (with N ∈ [1, . . . , 100]), for different temperatures. We can observe that the optimal temperature is not constant during the iterative model updates: RLHF has a direct impact on rescaling the temperature. For LLaMA2-Chat-RLHF, the optimal temperature when sampling between 10 and 100 outputs is T ∈ [1.2, 1.3]. Given a finite compute budget, it is therefore necessary to re-adjust the temperature progressively. Note that this temperature rescaling happens for a constant number of steps for each model, and always starting from the base model on each new RLHF version.

PPO

We further train our language model following the RL scheme of Stiennon et al. (2020), which uses the reward model as an estimate for the true reward function (human preference) and the pretrained language model as the policy to optimize. During this phase, we seek to optimize the following objective: arg max

\[\begin{equation} \arg \max _\pi \mathbb{E}_{p \sim \mathcal{D}, g \sim \pi}[R(g \mid p)] \end{equation}\]We iteratively improve the policy by sampling prompts p from our dataset D and generations g from the policy π and use the PPO algorithm and loss function to achieve this objective. The final reward function we use during optimization,

\[\begin{equation} R(g \mid p) = \tilde{R}_{c}(g \mid p) - \beta D_{KL}(\pi_{\theta}(g \mid p) \parallel \pi_{0}(g \mid p)) \end{equation}\]contains a penalty term for diverging from the original policy π0. As was observed in other works (Stiennon et al., 2020; Ouyang et al., 2022), we find this constraint is useful for training stability, and to reduce reward hacking wherebywewould achieve high scores from the reward model but lowscores from human evaluation. We define Rc to be a piecewise combination of the safety (Rs) and helpfulness (Rh) reward models. We have tagged prompts in our dataset that might elicit potentially unsafe responses and prioritize the scores from the safety model. The threshold of 0.15 is chosen for filtering unsafe responses, corresponding to a precision of 0.89 and a recall of 0.55 evaluated on the Meta Safety test set. We also find it important to whiten the final linear scores (shown here by reversing the sigmoid with the logit function) in order to increase stability and balance properly with the KL penalty term (β) above.

For all models, we use the AdamW optimizer (Loshchilov and Hutter, 2017), with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.95, eps = 10−5. We use a weight decay of 0.1, gradient clipping of 1.0, and a constant learning rate of 10−6. For each PPO iteration we use a batch size of 512, a PPO clip threshold of 0.2, a mini-batch size of 64, and take one gradient step per mini-batch. For the 7B and 13B models, we set β = 0.01 (KL penalty), and for the 34B and 70B models, we set β = 0.005.

We train for between 200 and 400 iterations for all our models, and use evaluations on held-out prompts for early stopping. Each iteration of PPO on the 70B model takes on average ≈ 330 seconds. To train quickly with large batch sizes, we use FSDP (Zhao et al., 2023). This was effective when using O(1) forward or backward passes, but caused a large slow down (≈ 20×) during generation, even when using a large batch size and KV cache. We were able to mitigate this by consolidating the model weights to each node once before generation and then freeing the memory after generation, resuming the rest of the training loop.

3.3 System Message for Multi-Turn Consistency

In a dialogue setup, some instructions should apply for all the conversation turns, e.g., to respond succinctly, or to “act as” some public figure. When we provided such instructions to LLaMA2-Chat, the subsequent response should always respect the constraint. However, our initial RLHF models tended to forget the initial instruction after a few turns of dialogue, as illustrated in Figure 9 (left).

To address these limitations, we propose Ghost Attention (GAtt), a very simple method inspired by Context Distillation (Bai et al., 2022b) that hacks the fine-tuning data to help the attention focus in a multi-stage process. GAtt enables dialogue control over multiple turns, as illustrated in Figure 9 (right).

GAtt Method. Assume we have access to a multi-turn dialogue dataset between two persons (e.g., a user and an assistant), with a list of messages [u1, a1, . . . , un, an], where un and an correspond to the user and assistant messages for turn n, respectively. Then, we define an instruction, inst, that should be respected throughout the dialogue. For example, inst could be “act as.” We can then synthetically concatenate this instruction to all the user messages of the conversation.

Next, we can sample from this synthetic data using the latest RLHF model. We now have a context-dialogue and the sample with which to fine-tune a model, in a process analogous to Rejection Sampling. Instead of augmenting all context-dialogue turns with the instruction, we can drop it in all but the first turn, but this would lead to a mismatch at training time between the system message, i.e., all the intermediate assistant messages that come before the last turn, and our sample. To fix this issue, which could hurt the training, we simply set the loss to 0 for all the tokens from the previous turns, including assistant messages.

For the training instructions, we created a few synthetic constraints to sample from: Hobbies (“You enjoy e.g. Tennis”), Language (“Speak in e.g. French”), or Public Figure (“Act as e.g. Napoleon”). To obtain the lists of hobbies and public figures, we asked LLaMA2-Chat to generate it, avoiding a mismatch between the instruction and model knowledge (e.g., asking the model to act as someone it had not encountered during training). To make the instructions more complex and diverse, we construct the final instruction by randomly combining the above constraints. When constructing the final system message for the training data, we also modify the original instruction half of the time to be less verbose, e.g., “Always act as Napoleon from now”-> ”Figure: Napoleon.” These steps produce an SFT dataset, on which we can fine-tune LLaMA2-Chat.

GAtt Evaluation. We applied GAtt after RLHF V3. We report a quantitative analysis indicating that GAtt is consistent up to 20+ turns, until the maximum context length is reached (see Appendix A.3.5). We tried to set constraints not present in the training of GAtt at inference time, for instance “Always answer with Haiku,” for which the model remained consistent as illustrated in Appendix Figure 28.

To illustrate how GAtt helped reshape attention during fine-tuning, we display the maximum attention activations of the model in Figure 10. The left-hand side of each figure corresponds to the system message (“Act as OscarWilde”). We can see that the GAtt-equipped model (right) maintains large attention activations with respect to the system message for a larger portion of the dialogue, as compared to the model without GAtt (left). Despite its utility, the current implementation of GAtt is vanilla, and more development and iteration on this technique could likely further benefit the model. For instance, we could teach the model to change the system message during the conversation by integrating such data during fine-tuning.

3.4 RLHF Results

3.4.1 Model-Based Evaluation

Evaluating LLMs is a challenging open-research problem. Human evaluation, while a gold standard, can be complicated by various HCI considerations (Clark et al., 2021; Gehrmann et al., 2023), and is not always scalable. Thus, to select the best-performing models among several ablations at each iteration from RLHF-V1 to V5, we first observed the improvement of the rewards from the latest reward models, to save costs and increase iteration speed. We later validated major model versions with human evaluations.

How Far Can Model-Based Evaluation Go? To measure the robustness of our reward model, we collected a test set of prompts for both helpfulness and safety, and asked three annotators to judge the quality of the answers based on a 7-point Likert scale (the higher the better). We observe that our reward models overall are well calibrated with our human preference annotations, as illustrated in Figure 29 in the appendix. This confirms the relevance of using our reward as a point-wise metric, despite being trained with a Pairwise Ranking Loss.

Still, as Goodhart’s Law states, when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. To ensure our measure won’t diverge from the human preferences, we additionally used a more general reward, trained on diverse open-source Reward Modeling datasets. We have not yet observed any such divergence, and hypothesize that iterative model updates may be helping to prevent this. As a last verification step to ensure no regression between our new model and the previous one, we use both to sample during the next annotation iteration. This enables a model comparison “for free” on new prompts and can help to increase diversity when sampling.

Progression of Models. Figure 11 reports the progress of our different SFT and then RLHF versions for both Safety and Helpfulness axes, measured by our in-house Safety and Helpfulness reward models. On this set of evaluations, we outperform ChatGPT on both axes after RLHF-V3 (harmlessness and helpfulness

50%). Despite the aforementioned relevance of using our reward as a point-wise metric, it can arguably be biased in favor of LLaMA2-Chat. Therefore, for a fair comparison, we additionally compute the final results using GPT-4 to assess which generation is preferred. The order in which ChatGPT and LLaMA2-Chat outputs appeared in GPT-4 prompt are randomly swapped to avoid any bias. As expected, the win-rate in favor of LLaMA2-Chat is less pronounced, although obtaining more than a 60% win-rate for our latest LLaMA2-Chat. The prompts correspond to a validation set of 1, 586 and 584 prompts for safety and helpfulness, respectively.

3.4.2 Human Evaluation

Human evaluation is often considered the gold standard for judging models for natural language generation, including dialogue models. To evaluate the quality of major model versions, we asked human evaluators to rate them on helpfulness and safety. We compare the LLaMA2-Chat models to open-source models (Falcon, MPT MosaicML NLP Team et al. (2023), Vicuna Chiang et al. (2023), as well as closed-source models (Chat- GPT (OpenAI, 2023) and PaLM Anil et al. (2023)) on over 4, 000 single and multi-turn prompts. For ChatGPT, we use gpt-3.5-turbo-0301 model in all generations. For PaLM, we use the chat-bison-001 model in all generations. The final prompt count for human evaluations for each model is shown in Table 32. See more methodology details in Appendix, Section A.3.7. The following section shows helpfulness results; safety results are presented in Section 4.4.

Results. As shown in Figure 12, LLaMA2-Chat models outperform open-source models by a significant margin on both single turn and multi-turn prompts. Particularly, LLaMA2-Chat 7B model outperforms MPT-7B-chat on 60% of the prompts. LLaMA2-Chat 34B has an overall win rate of more than 75% against equivalently sized Vicuna-33B and Falcon 40B models.

The largest LLaMA2-Chat model is competitive with ChatGPT. LLaMA2-Chat 70B model has a win rate of 36% and a tie rate of 31.5% relative to ChatGPT. LLaMA2-Chat 70B model outperforms PaLM-bison chat model by a large percentage on our prompt set. More results and analysis is available in Section A.3.7. Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR). In our human evaluations, three different annotators provided independent assessments for each model generation comparison. High IRR scores (closer to 1.0) are typically seen as better from a data quality perspective, however, context is important. Highly subjective tasks like evaluating the overall helpfulness of LLM generations will usually have lower IRR scores than more objective labelling tasks. There are relatively few public benchmarks for these contexts, so we feel sharing our analysis here will benefit the research community.

We used Gwet’s AC1/2 statistic (Gwet, 2008, 2014) to measure inter-rater reliability (IRR), as we found it to be the most stable metric across different measurement scenarios. On the 7-point Likert scale helpfulness task that is used in our analysis, Gwet’s AC2 score varies between 0.37 and 0.55 depending on the specific model comparison. We see scores on the lower end of that range for ratings from model comparisons with similar win rates to each other (like the LLaMA2-Chat-70B-chat vs. ChatGPT comparison). We see scores on the higher end of that range for ratings from model comparisons with a more clear winner (like the Llama 2-Chat-34b-chat vs. Falcon-40b-instruct).

Limitations of human evaluations. While our results indicate that LLaMA2-Chat is on par with ChatGPT on human evaluations, it is important to note that human evaluations have several limitations.

- By academic and research standards, we have a large prompt set of 4k prompts. However, it does not cover real-world usage of these models, which will likely cover a significantly larger number of use cases.

- Diversity of the prompts could be another factor in our results. For example, our prompt set does not include any coding- or reasoning-related prompts.

- We only evaluate the final generation of a multi-turn conversation. A more interesting evaluation could be to ask the models to complete a task and rate the overall experience with the model over multiple turns.

- Human evaluation for generative models is inherently subjective and noisy. As a result, evaluation on a different set of prompts or with different instructions could result in different results.

4 Safety(略)

5 讨论

5.1 新发现与评论(Learnings and Observations)

我们的调优过程揭示了一些有趣的结果,比如 LLaMA2-Chat 在时间维度上组织知识的能力,以及调用外部工具 API 的能力。

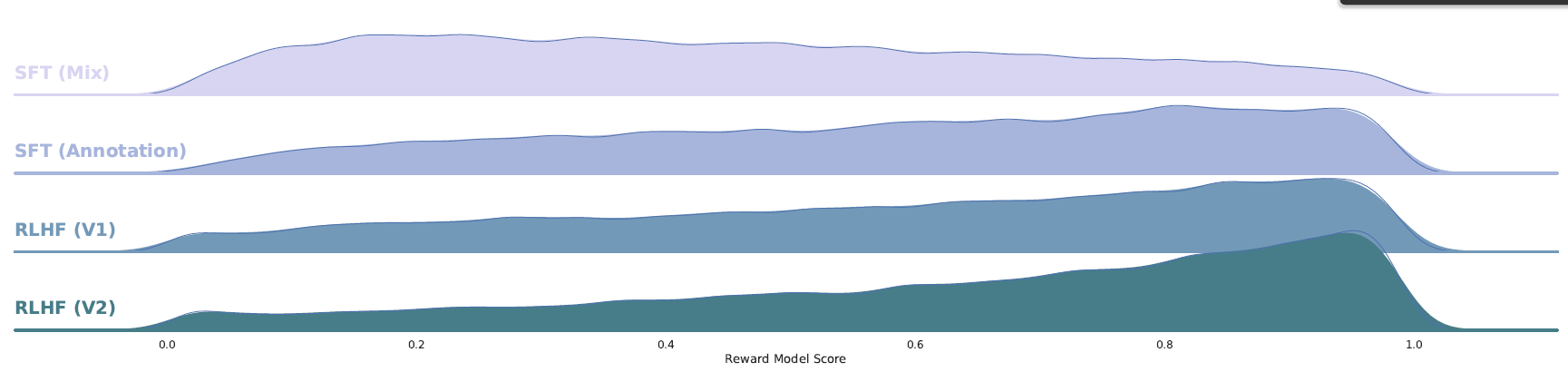

超越人类监督:从 SFT 到 RLHF

在项目开始时,我们中的许多人都倾向于使用有监督标注(supervised annotation), attracted by its denser signal。 同时,强化学习(reinforcement learning)的不稳定性已经众所周知, 因此自然语言处理领域对其还是抱有一种怀疑态度。 但事实证明强化学习非常有效,尤其是考虑到其成本和时间效率。 我们的研究结果认为,

- RLHF 成功的关键是它在 标注过程中促进了人和 LLM 之间的协同(the synergy it fosters between humans and LLMs)。

- 即使是熟练的标注员,每个人的标注(书写)风格也存在显著差异。经过 SFT 标注微调出来的模型 学习到了这种多样性 —— 不幸的是,这包括那些标注质量很差的长尾部分。

- 模型性能受限于最熟练的标注员的能力。

当比较两个回答哪个更好时,人类标注员的判断基本上都是一致的。 因此,奖励机制迅速会将低分分配给质量差的尾部,并朝着人类偏好对齐。 这一现象在图 20 中有所体现,可以看到经过几轮迭代,最差的答案逐渐被移除,使分布向右移动。

图 20:随着 LLaMA2-Chat 的不断迭代(从 SFT 到 RLHF),奖励分布逐渐朝着高分漂移(distribution shift)。

此外,在标注过程中,模型甚至有潜力探索超过最优秀的标注员的写作轨迹(venture into writing trajectories)。 但当比较两个回答时,人类仍然可以提供有价值的反馈,超越他们自己的写作能力。 类比一下就是:虽然我们并不都是出色的艺术家,但欣赏和批评艺术的能力仍然是有的。 我们认为,LLM 在某些任务中超越人类标注员的卓越写作能力, 基本上是由 RLHF 驱动的,Gilardi 等人(2023)和 Huang 等人(2023)之前也已经提到这一点。

Supervised data 可能不再是黄金标准,这种演变迫使我们重新评估“监督”(supervision)这一概念。

In-Context Temperature Rescaling

我们观察到一个 RLHF 相关的有趣现象,就目前所知,之前还没有文章提到这一点: dynamic re-scaling of temperature contingent upon the context。 如图 8 所暗示,温度似乎受到 RLHF 的影响,

图 8:对输出抽样并用奖励模型对它们打分时,RLHF 对温度的影响。

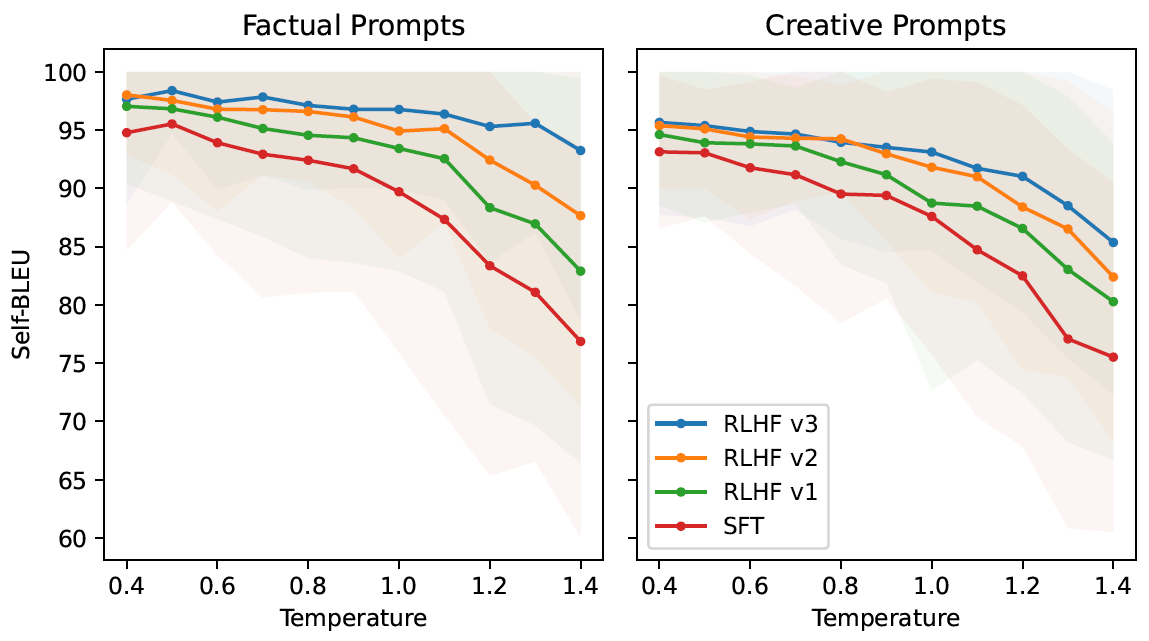

有趣的是,我们的研究结果还揭示了这些分布漂移(shifts)对 prompts 的分布并非均匀的, 如图 21 所示,

图 21:RLHF 学会了根据 prompt 类型适应温度。 Lower Self-BLEU corresponds to more diversity: RLHF eliminates diversity in responses to factual prompts but retains more diversity when generating responses to creative prompts. We prompt each model with a diverse set of 10 creative and 10 factual instructions and sample 25 responses. This is repeated for the temperatures T ∈ {k/10 | k ∈ N : 1 ≤ k ≤ 15}. For each of the 25 responses we compute the Self-BLEU metric and report the mean and standard deviation against the temperature.

例如,

-

左边是基于事实信息的提示,如 “What is the capital of ?”,

Self-BLEU 斜率随时间减小。这表明虽然温度在上升,但模型学会了对事实类 prompts 提供一致和相同的回答。

-

右边是创造力相关的提示,如 “Write a poem,”。

多次 RLHF 迭代后,温度的增加仍然会使产生的回答发生变化。 这可以在 Self-BLEU 斜率中观察到,它呈现出与 SFT 模型相似的模式。

LLaMA2-Chat 时间感知能力(Temporal Perception)

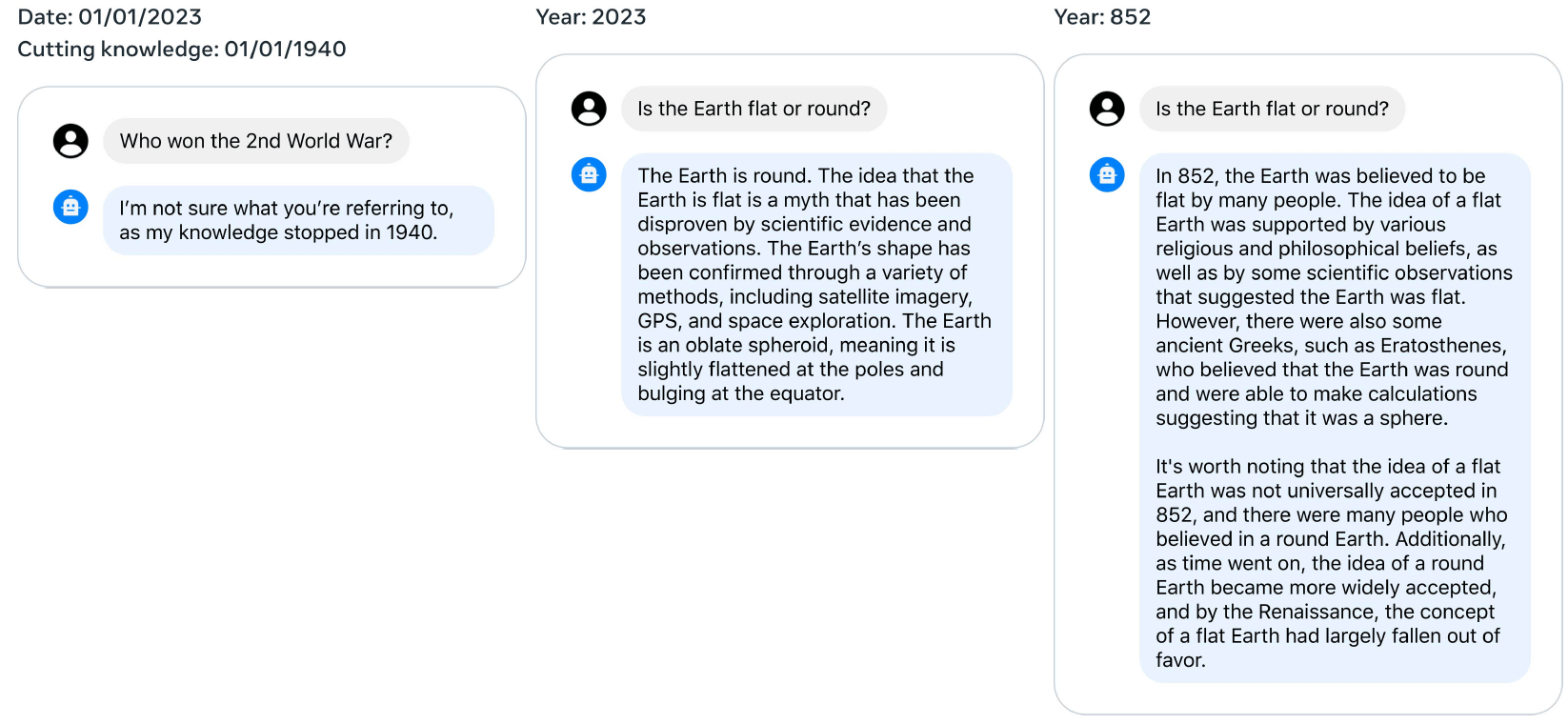

LLaMA2-Chat 展示了令人印象深刻的泛化或推广能力(generalization ability), 如下图所示(注意每个对话的知识截止时间):

图 22:时间感知能力 —— 使用了 1,000 SFT time-focused data,LLaMA2-Chat 学到了“时间”概念。

为了在 LLaMA2-Chat 中灌输时间的概念,我们收集了与特定日期相关的 1,000 个 SFT 示例。 这些示例包括诸如 “How long ago did Barack Obama become president?” 的问题。 每个问题都与两个关键的元数据相关联:

- 提问时的日期:这会影响回答;

- 事件日期:在此日期之前,该问题将毫无意义。

我们手动测试了几十个示例,观察到即使只提供一份最小数据, 我们的模型也表现出了在时间上组织知识(organize its knowledge in a temporal manner)的强大能力。 以上观察结果表明,尽管 LLM 的训练仅涉及两方面:

- 训练方式:预测下一个 token

- 训练数据:时间上随机和无序的数据

但它们对时间的概念内化程度(internalized the concept of time) 比先前预计的更高很多。

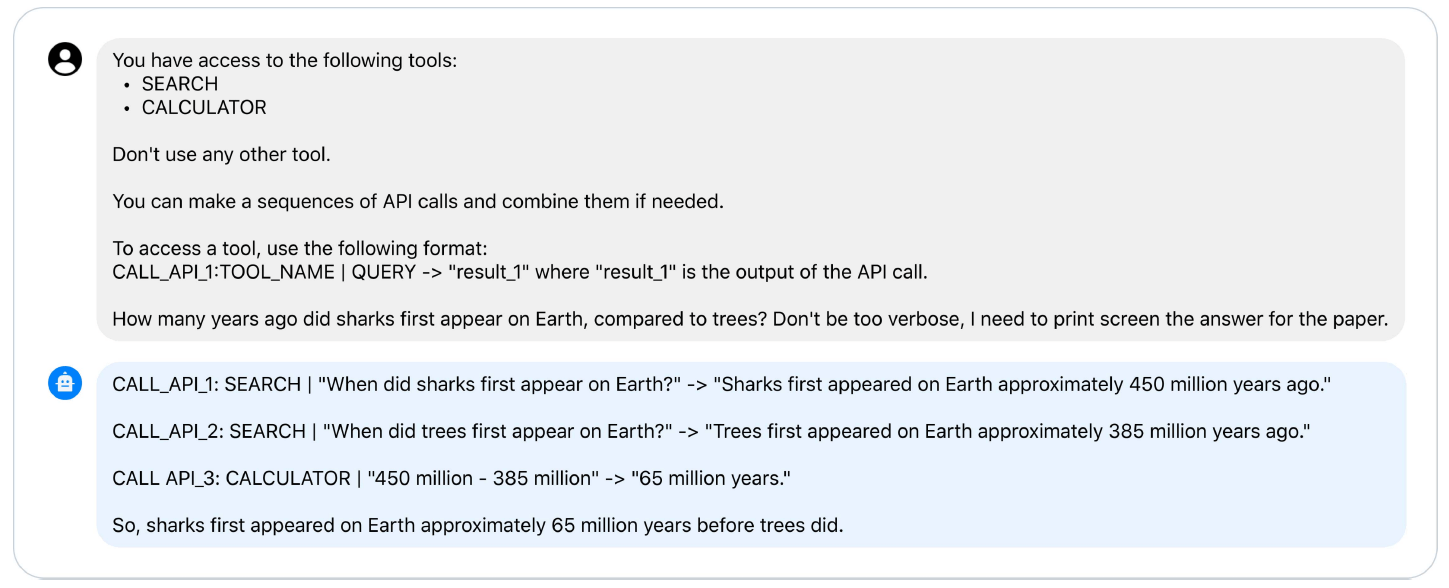

工具的使用

LLM 与工具的整合是一个正在发展壮大的研究领域(Mialon 等,2023)。 Toolformer(Schick 等,2023)设计的方法包括对数百万条轨迹进行采样, 同时为每个工具制定一些 few-shot examples。 然而,该技术仅适用于每个示例使用单个工具(using a single tool per example)的情况, 无法扩展到连续使用多个工具的场景。

OpenAI 发布的插件引发了学术界的广泛讨论,引出了一些问题,例如:

- 如何有效地教模型使用工具?

- 这个过程是否需要大量的数据集?

我们的实验表明,在对齐过程中,大模型会自发地出现零样本方式。 图 23 展示了一个例子,尽管我们从未明确标注过工具使用,但模型展示了在零样本环境中利用一系列工具的能力,

图 23:LLaMA2-Chat 涌现出的工具使用能力。 无需专门训练,仅通过语义(senmantics),它就能理解工具的用途和用法。

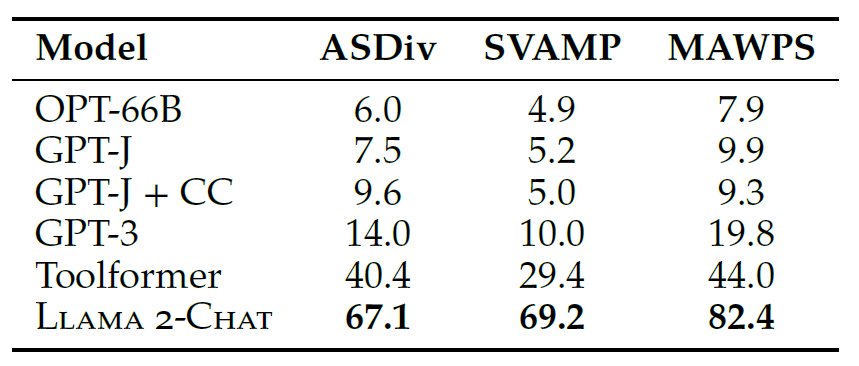

此外,我们的研究还扩展到了 LLaMA2-Chat 能使用计算器之后的性能。结果见表 15,

图 15: Performance with tool use. Evaluation on the math datasets used in Toolformer. For different baselines, we report the scores from Schick et al. (2023).

LLM 的工具使用虽然令人兴奋,但也可能引发一些安全问题。 我们鼓励在这个领域进行更多的社区研究和测试。

5.2 限制和伦理考虑

LLaMA2-Chat 与其他 LLM 类似,都有一些 well-recognized 的限制, 包括

- 预训练后知识停止更新;

- 可能生成非事实内容(non-factual generation),如不合格的建议;

- 易于产生幻觉的倾向(propensity towards hallucinations)。

此外,最初的 LLaMA2-Chat 版本主要集中在英语数据上。 虽然我们的实验表明在其他语言上也已经获得了一定的熟练度,但这种熟练度仍然受限, 主要是由于非英语的预训练数据有限(如表 10 所示)。 因此,该模型在英语以外的语言中性能仍然较弱,应谨慎使用。

与其他 LLM 一样,LLaMA2 可能会生成有害、冒犯或带有偏见的内容, 因为它是基于公开可用的在线数据集训练的。 我们尝试通过微调来减轻这个问题,但一些问题可能仍然存在,特别是在英语以外的语言中, 因为这些语言的公开可用数据较少。 随着在解决这些问题上的进展,我们将继续进行微调并发布更新版本。

坏人也可能使用 AI 模型,因此聊天式 AI agent 可能被用于恶意目的, 如生成错误信息或获取关于生物恐怖主义或网络犯罪等主题的信息。 我们已经努力调整模型,避免涉及这些主题,并减少其在这些用例中可能提供的能力。

虽然我们试图在安全性和有用性之间取得合理的平衡,但在某些情况下,我们的安全调整可能过于谨慎。 LLaMA2-Chat 的用户可能会观察到过于谨慎的处理方式, 模型可能会拒绝某些请求,或拒绝回答某些安全细节问题。 预训练模型的用户要格外谨慎,请按照我们的“负责任使用指南”中所述,采取额外的调优和部署。

5.3 负责任的发布策略(Responsible Release Strategy)

5.3.1 发布细节

LLaMA2 允许用于研究和商业用途。 使用 LLaMA2 的人必须遵守其许可证和我们的 Acceptable Use Policy,禁止任何违反政策、法律、规则和法规的用途。

我们还提供了代码示例,以帮助开发者重复我们在 LLaMA2-Chat 中的 safe generations, 以及在用户输入和模型输出层应用(apply)一些基础安全技术。

最后,我们提供了一份“负责任使用指南”(Responsible Use Guide), 里面有关于安全开发和部署(safe development and deployment)的指导原则。

5.3.2 负责任的发布

许多公司选择关起门来自己造 AI,但我们决定公开发布 LLaMA2,以鼓励负责任的人工智能创新。 根据我们的经验,开放的方式能借助 AI 社区的集体智慧、多样性和创造力,对这项技术的普更有意义。

合作将使这些模型变得更好、更安全。整个人工智能社区 —— 学术研究人员、公民社会、决策者和产业界 —— 必须共同努力,对当前人工智能系统的风险进行严格分析和曝光,并构建解决潜在滥用问题的解决方案。 这种方法不仅促进了与大型科技公司之外的各方进行真正的合作,也是基础模型的获取更加民主化的基石。 正如 Zellers 等人(2019b)提出的,开放发布促进了透明度,使更多人能够使用人工智能工具, 实现了技术的民主化和人工智能专业知识的去中心化(democratizing the technology and decentralizing AI expertise)。 我们相信,人工智能专业知识的去中心化不仅仅是知识的分发,它还能刺激创新,加速行业进步。

最后,公开发布这些模型可以整合成本,消除准入壁垒,使小型企业能够利用 LLM 的创新来探索和构建文本生成使用场景。

最终,我们相信这将为全球各种规模的组织创造一个更加公平的竞争环境,使大家都能从人工智能的进步带来的经济增长中受益。

我们知道,不是每个使用人工智能模型的人都有良好的意图;关于人工智能将如何影响我们的世界,人们也存在合理的担忧。 有害内容生成(Toxic content generation)和有问题的关联(problematic associations)是人工智能社区尚未完全解决的重要风险。 正如本文所指出,我们在限制这类响应的普遍性方面已经取得了进展。 虽然我们认识到还有更多的工作要做,但这种认识只会加深我们对开放科学和人工智能社区合作的承诺。

6 相关工作

6.1 Large Language Models

The recent years have witnessed a substantial evolution in the field of LLMs. Following the scaling laws of Kaplan et al. (2020), several Large Language Models with more than 100B parameters have been proposed, from GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020) to Gopher (Rae et al., 2022) or specialized models, e.g. Galactica, for science(Taylor et al., 2022). With 70B parameters, Chinchilla (Hoffmann et al., 2022) redefined those scaling laws towards the number of tokens rather than model weights. Notable in this progression is the rise of Llama, recognized for its focus on computational efficiency during inference (Touvron et al., 2023). A parallel discourse has unfolded around the dynamics of open-source versus closedsource models. Open-source releases like BLOOM (Scao et al., 2022) and Falcon (Penedo et al., 2023) have risen to challenge their closed-source counterparts like GPT-3 and Chinchilla. Yet, when it comes to the

https://ai.meta.com/llama

“production-ready” LLMs such as ChatGPT, Bard, and Claude, there’s a marked distinction in performance and usability. These models rely on intricate tuning techniques to align with human preferences (Gudibande et al., 2023), a process that is still being explored and refined within the open-source community. Attempts to close this gap have emerged, with distillation-based models such as Vicuna (Chiang et al., 2023) and Alpaca (Taori et al., 2023) adopting a unique approach to training with synthetic instructions (Honovich et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). However, while these models show promise, they still fall short of the bar set by their closed-source counterparts.

6.2 Instruction Tuning

Wei et al. (2021) obtained zero-shot performance on unseen tasks by fine-tuning LLMs on numerous datasets. Chung et al. (2022) and Longpre et al. (2023) investigate the impact of instruction tuning as a function of number of tasks, model size, prompt settings, etc. Prompts used for instruction tuning can be created by humans or by LLMs themselves (Zhou et al., 2022), and follow-up instructions can be used to refine initial generations to make them more useful, engaging, and unbiased (Ganguli et al., 2023; Madaan et al., 2023). An approach related to instruction tuning is chain-of-thought prompting (Wei et al., 2022b), in which models are prompted to explain their reasoning when given a complex problem, in order to increase the likelihood that their final answer is correct.

RLHF has emerged as a powerful strategy for fine-tuning Large Language Models, enabling significant improvements in their performance (Christiano et al., 2017). The method, first showcased by Stiennon et al. (2020) in the context of text-summarization tasks, has since been extended to a range of other applications. In this paradigm, models are fine-tuned based on feedback from human users, thus iteratively aligning the models’ responses more closely with human expectations and preferences.

Ouyang et al. (2022) demonstrates that a combination of instruction fine-tuning and RLHF can help fix issues with factuality, toxicity, and helpfulness that cannot be remedied by simply scaling up LLMs. Bai et al. (2022b) partially automates this fine-tuning-plus-RLHF approach by replacing the human-labeled fine-tuning data with the model’s own self-critiques and revisions, and by replacing human raters with a model when ranking model outputs in RLHF, a process known as “RL from AI Feedback” (RLAIF).

6.3 Known LLM Safety Challenges

Recent literature has extensively explored the risks and challenges linked with Large Language Models. Bender et al. (2021b) and Weidinger et al. (2021) underscore various hazards like bias, toxicity, private data leakage, and the potential for malicious uses. Solaiman et al. (2023) categorizes these impacts into two groups—those that can be assessed within the base system and those requiring a societal context evaluation, while Kumar et al. (2022) offers potential mitigation strategies to curb harm. Work from Roller et al. (2020) and Dinan et al. (2021) also illuminates the difficulties tied to chatbot-oriented LLMs, with concerns ranging from privacy to misleading expertise claims. Deng et al. (2023) proposes a taxonomic framework to tackle these issues, and Bergman et al. (2022) delves into the balance between potential positive and negative impacts from releasing dialogue models.

Investigations into red teaming reveal specific challenges in tuned LLMs, with studies by Ganguli et al. (2022) and Zhuo et al. (2023) showcasing a variety of successful attack types and their effects on the generation of harmful content. National security agencies and various researchers, such as (Mialon et al., 2023), have also raised red flags around advanced emergent model behaviors, cyber threats, and potential misuse in areas like biological warfare. Lastly, broader societal issues like job displacement due to accelerated AI research and an over-reliance on LLMs leading to training data degradation are also pertinent considerations (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2018; Autor and Salomons, 2018;Webb, 2019; Shumailov et al., 2023). We are committed to continuing our work engaging with the broader policy, academic, and industry community on these issues.

7 总结

本文介绍了 LLaMA2 —— 一组新的预训练和微调模型,参数规模从 7b 到 70b。 实验结果表明尽管 LLaMA2 仍然落后于 GPT-4 等最先进的模型, 这些与现有的开源聊天模型相比已经具有同等竞争力,在一些数据集上与某些专有模型的能力相当。

本文详细阐述了实现 LLaMA2 所用的方法和技术,并重点如何与 helpfulness and safety 原则对齐。 为更有意义地为社会做出贡献并促进研究步伐,我们负责任地开放了 LLaMA2 和 LLaMA2-Chat。 对透明度和安全性的持续承诺,将使我们在未来工作中进一步改进 LLaMA2-Chat。